Democrat John Gregg, left, and Republican Eric Holcomb, right, squared off in their first debate Sept. 27. Libertarian Rex Bell joined the discussion as well. (AP photo)

Both Gregg, Holcomb favor ‘all-of-the-above’ energy strategy

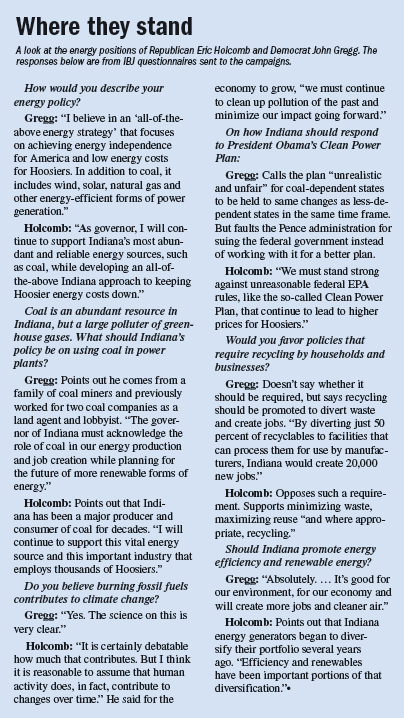

The race for governor has focused heavily on jobs, education and social issues such as gay rights and abortion.

But another topic, energy, is just as likely to affect the daily habits and wallets of every Indiana household andthousands of businesses, from sprawling factories to the corner drugstore.

The next governor’s energy policy could shape whether Indiana remains a coal-dependent state or instead promotes energy efficiency, clean energy sources and recycling—a direction in which many states are moving and one that’s touted by some as the energy job frontier.

But based on their records and campaign promises, neither Democrat John Gregg nor Republican Eric Holcomb seems likely to radically reshape Indiana’s energy policies.

Both support the use of coal, abundant in Indiana, as a fuel source for electricity, even as many other states are moving more quickly to encourage the use of clean, renewable fuel sources, such as wind and solar power.

But when questioned about whether they believe that burning fossil fuels contributes to climate change, they differ.

“Yes, the science on this is very clear,” Gregg said.

Holcomb said he was less certain. “It is certainly debatable how much that contributes,” he said. “But I think it is reasonable to assume that human activity does, in fact, contribute to changes over time.”

They both use the phrase “all of the above” to describe their energy goals, meaning they support use of renewables but still back the use of coal, a controversial fuel source that emits greenhouse gases and that most scientists say contributes to climate change.

“As governor, I will continue to support Indiana’s most abundant and reliable energy sources, such as coal, while developing an all-of-the-above Indiana approach to keeping Hoosier energy costs down,” Holcomb said.

Gregg, a former land agent for Peabody Coal and lobbyist for Amax Coal, comes from a family of coal miners, and said he squarely stands behind coal, while approving of other fuel sources.

“I believe in an ‘all-of-the-above’ energy strategy that focuses on achieving energy independence for America and low energy costs for Hoosiers,” he said.

Energy is a big business in Indiana. The state, which leads the nation in manufacturing as a percent of the state economy, uses an outsized amount of energy to power auto-assembly plants, oil refineries, chemical plants, hospitals, printing plants and millions of households.

So while Indiana is only 16th in the nation in population, it ranks 9th per capita in use of energy, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

All that adds up to huge sums in energy costs each year.

“From our perspective, energy is certainly an important issue to Indiana,” said Bette Dodd, director of the Indiana Industrial Energy Consumers Inc., which represents large buyers, such as General Motors and Allison Transmission.

When coal was cheap, Hoosiers enjoyed low prices, the organization said. Indiana ranked 5th-lowest in the nation for electricity prices in 2003. But as other fuel sources became cheaper and environmental rules made coal more expensive to burn, that advantage slipped, pushing Indiana to 23rd place in 2013.

However, because most of the energy is produced in coal-fired power plants, Indiana is also a leader in pollution, ranking 3rd in emissions for nitrogen oxide, 4th for sulfur dioxide and 5th for carbon dioxide. Those emissions have been linked to a wide variety of health ailments, from breathing problems to heart disease.

In the meantime, Indiana ranks a lowly 38th for use of renewable and alternative fuels and 42nd for energy efficiency.

For more than two years, Gov. Mike Pence has battled the Obama administration over the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Clean Power Plan, which calls for sweeping new requirements to cut carbon dioxide emissions 32 percent below 2005 levels by 2030.

The plan’s goal is to shift the nation to cleaner energy and require states to meet specific standards for carbon emissions.

But Pence has declared that his administration will not comply and has joined 26 other states that have sued the federal government to keep the rules from taking effect. A federal appeals court heard arguments in late September.

“Indiana is a pro-coal state, and we must continue to oppose the overreaching schemes of the EPA until we bring this war on coal to an end,” Pence said in his State of the State address in 2015.

In the meantime, Indiana has slowly begun to diversify into other fuel sources. In 1998, coal-burning power plants accounted for 98 percent of the utility-generated electricity in Indiana. By 2014, that number had shrunk to85 percent.

And that number is certain to drop even further soon. Indianapolis Power and Light Co.’s Harding Street power plant, which once burned 2 million tons of coal a year, converted to natural gas earlier this year. IPL is also retiring six coal-fired units at its Eagle Valley Generating Station near Martinsville, replacing them with a 650-megawatt combined-cycle gas turbine.

Other utilities are considering similar moves. The Northern Indiana Public Service Co., for example, recently said it might retire four coal-burning power plants, or about half of its coal-fired capacity, by 2023.

“The fact is, we are shifting away from coal as a state,” said Mark Maassell, president of the Indiana Energy Association, a trade group that represents electric power and natural gas companies.

But Indiana—which once kept many thousands of people employed in coal mines and related businesses—has been slower to leave its energy roots. Tennessee, Texas, Idaho, Oklahoma and other conservative states all rank higher than Indiana in electricity generation from renewables, such as wind and solar.

Political attacks

Despite Gregg’s prior work for coal companies, the Republican Governors Association has been trying to cast him as an enemy of the industry, running ads tying him to presidential candidate Hillary Clinton.

One commercial calls Gregg a big supporter of Clinton. Then it cuts to footage of Clinton declaring, “We’re going to put a lot of coal miners and coal companies out of business.”

Gregg has taken pains to distance himself from Obama’s environmental policies, and by extension, from Clinton’s remarks.

“As I’ve said in the past, I disagree with President Obama on the Clean Power Plan,” Gregg said. “I believe it’s unrealistic and unfair for a coal-dependent state such as Indiana to make the same changes as less coal-dependent states in the same quick timeframe.”

However, Gregg is taking issue with Pence’s strategy of mounting a frontal assault on Obama’s Clean Power Plan, saying the state should have worked with the federal government in developing a better plan rather than filing suit.

In criticizing Pence, Gregg loops in Holcomb, who has been lieutenant governor since March.

“The Pence/Holcomb administration’s determination to put politics ahead of responsible governing risks Hoosier jobs and economic opportunity,” Gregg said. “It is yet another example of failed leadership that results from a focus on ideology and partisan politics.”

Holcomb, for his part, defended Pence’s strategy.

“We must stand strong against unreasonable federal EPA rules, like the so-called Clean Power Plan, that continue to lead to higher prices for Hoosiers.”

‘Greatly concerned’

Like Pence, Holcomb is challenging federal rules that he says will hurt the coal industry. In early September, he wrote to the U.S. Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement, asking it to reject a proposed rule that would strengthen the regulation of waterways around surface mines.

“I am greatly concerned that this proposed rule will adversely impact our important coal industry and subsequently hamper [Indiana’s] continued economic growth,” he wrote.

The bickering, meanwhile, has turned off some energy and environmental leaders across Indiana, who say the candidates should be focusing on constructive, state-level policies that will move the economy and environment forward.

Jesse Kharbanda, executive director of the not-for-profit Hoosier Environmental Council, points out that there are more than twice as many jobs in the nation’s solar industry alone than in the coal mining sector. The state should be pushing to encourage those types of jobs, which are likely to be around for decades, he said.

“When it comes to energy issues, the governor’s race ought to focus on what it will take for Indiana to have the biggest slice possible in the astonishingly large clean energy job sector,” he said.

Jodi Perras, head of the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal Campaign in Indiana, said the next governor needs to recognize that coal is on an “irreversible downward trend” and take the lead on other sources, as many other states are doing.

Wind generation, for example, already exceeds 10 percent of energy generation in 11 states, but remains in the single digits in Indiana. She pointed out that numerous Indiana employers have pledged to achieve 100 percent renewable energy, including General Motors, Salesforce, Walmart and Nestle.

“We could be exporting wind power and generating affordable solar power right here in Indiana, if we had the right leadership,” she said.

Still, wind power is a growing force here. Although it accounts for just5.5 percent of Indiana’s energy production, the state ranks fifth nationally for installed wind power capacity.

And some point out that moving Indiana from its coal roots to alternative sources can’t help but take time.

“It can take years and decades to build additional baseload and move away from a certain energy source,” said Brian Burton, president and CEO of the Indiana Manufacturers Association. “You have to do it in a cost-effective manner that doesn’t shock the system.”

Moving backward?

Some environmentalists point wistfully to Gov. Mitch Daniels’ administration, which they say represented a high point for clean energy. Daniels created energy-efficiency goals in 2009 that led to the creating of Energizing Indiana, a statewide program for helping households and businesses cut energy costs.

In 2015, he launched BioTown USA in the small town of Reynolds, which helped farms take gas from manure to make electricity. He also helped make Indiana one of the fastest-growing states for commercial wind installations from 2008 to 2011. And in 2011 he updated rules that led to a significant increase in customer-owned solar power installations.

“Mitch Daniels was the best friend clean energy ever had in the state of Indiana,” said Kerwin Olson, executive director of Citizens Action Coalition, a grassroots environmental group.

By comparison, Pence has allowed Daniels’ Energizing Indiana program to shut down and the energy efficiency goals to be repealed. Since Daniels left office, Indiana has fallen from 27th to 42nd place for energy efficiency, according to the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy in Washington, D.C.

The next governor will get to decide how important energy issues are to Indiana, and to push the state in one direction or the other.

“Indiana’s energy landscape is already changing dramatically, yet the state is failing to plan for that transition,” Perras said